Avoid These 4 Psychological Pitfalls for Better Project Outcomes

👋 Welcome to The Influential Project Manager, a weekly newsletter covering the essentials of successful project leadership.

Today’s Overview:

A psychological fallacy, also known as a cognitive fallacy, is a mistaken belief or flawed reasoning that occurs due to the way our brains process information.

In any large scale project - meaning a project that is considered big, complex, ambitious, and risky by those in charge - people are required to think, make judgements, and reach decisions. In these situations, psychological factors and power dynamics inevitably come into play.

To help you be more aware of these forces at play, we'll discuss 4 common psychological fallacies to avoid for better project results.

Today's projects, whether big or small, can be complex and overwhelming, challenging our emotions and rational thinking.

At the heart of these projects are people thinking and making decisions, influenced by psychology and power dynamics. After recognizing patterns in how different projects unfold, we can better understand the underlying forces at play.

This essay aims to help you become more aware of these forces by exploring three common psychological fallacies that, if avoided, can lead to improved project outcomes.

Psychology and power drive projects at all scales, from skyscrapers to kitchen renovations. They are found whenever someone is excited by a vision and wants to turn it into a plan and make that plan a reality.

Modern psychology reveals that human decision-making relies on two systems: "System One," which focuses on quick, intuitive judgments, and "System Two," which involves conscious reasoning. The main difference between the two is their speed.

System One:

Operates fast

Makes snap judgments

System Two:

Operates slowly

Allows for a more deliberate thought process.

Both systems can be right or wrong. After System One delivers a quick judgment, we can take the time to think more carefully using System Two and adjust or override the initial decision.

Influential Project Managers excel because they comprehend the psychological forces at play and manage to avoid them. They recognize that human psychology and behavioral biases always have an impact, particularly when the stakes and complexity are high.

This realization reveals a crucial truth for project managers that might be hard to accept, but once acknowledged, it can be liberating:

Know that your biggest risk is YOU.

It’s tempting to think that project’s fail because the world throws surprises at us: price and scope changes, accidents, weather, or new management. But this is shallow thinking.

History shows that projects often fail because people succumb to biases or logical fallacies, choosing to disregard truths or follow flawed reasoning. The greatest threat you face isn't external; it lies within your own biases and thought patterns. This holds true for every one of us and for every project.

What is a Psychological Fallacy?

A psychological fallacy, also known as a cognitive fallacy, is a mistaken belief or flawed reasoning that occurs due to the way our brains process information.

It's important to understand that our brains are not perfect, and they often use mental shortcuts or biases to help us make quick decisions in everyday life. However, these shortcuts can sometimes lead to errors in judgment or incorrect conclusions.

In simple terms, a psychological fallacy occurs when our brain takes a mental shortcut that results in an incorrect or illogical conclusion. These fallacies can be influenced by our emotions, experiences, and the way we perceive the world around us. They can affect our decision-making, problem-solving, and how we understand and interact with others.

There are many types of fallacies, but some common examples include:

Confirmation Bias: the tendency to search for, interpret, or remember information in a way that confirms our preexisting beliefs or opinions.

Bandwagon effect: the tendency to adopt the beliefs or behaviors of others because we assume that if many people are doing something, it must be correct or valid.

Ad hominem: Attacking a person's character or motives instead of addressing their argument.

Straw man: Misrepresenting an opponent's argument to make it easier to criticize or refute.

Appeal to authority: Using an expert's opinion as evidence even when it's irrelevant or the expert isn't qualified in the topic being discussed.

False cause: Assuming that because two events occurred together or in sequence, one must have caused the other.

Slippery slope: Claiming that a small step in a particular direction will inevitably lead to disastrous consequences without providing evidence.

Today, I'll be discussing 4 specific fallacies that are commonly encountered in projects, which you can proactively avoid.

The Optimism Bias

The Commitment Fallacy

The Sunk Cost Fallacy

What you see is all there is (“WYSIATI”)

I personally come across these on a regular basis. I've observed project managers who get trapped in these fallacies, as well as those who recognize and overcome them. Project managers who are aware of their biases consistently achieve greater success and wield more influence.

1. The Optimism Bias

The Optimism Bias is our tendency to believe that we're less likely to experience negative events compared to others. It's like our mind's way of telling us that everything will turn out okay, even when faced with evidence to the contrary. It's like always seeing the glass as half full, even when it might not be.

This bias is naturally wired into us because it helps us to keep pushing forward. By focusing on the positive and downplaying the negative, we're motivated to take on challenges, which in turn helps us survive and thrive.

Examples of the optimism bias include:

Project Timeline: A construction manager might underestimate the time required to complete a project based on overly optimistic assessments of productivity, efficiency, or perfect conditions. For example, they might assume that there will be no delays due to weather, no issues with subcontractors, or no design changes.

Budget Estimation: Another common example is underestimating the project's cost. Construction managers might believe they can complete the project under budget, even when historical data or industry standards suggest a higher cost.

“It won’t happen to me; it only happens to others.”

To avoid the optimism bias:

Use Objective Data: Make decisions based on empirical data and historical performance, rather than on personal beliefs or gut feelings. For example, use past project performance to estimate timelines and costs more accurately.

Implement a Review Process: Encourage regular reviews and audits of project plans and progress. This allows for more eyes on the project, which can help catch overoptimistic assumptions and adjust plans as needed. Also, consider getting feedback from external experts who can provide an unbiased perspective.

2. The Commitment Fallacy

The Commitment Fallacy is a cognitive bias that describes the tendency of an individual to remain committed to past behaviors - even if they result in undesirable outcomes. This fallacy leads individuals to stick with a failing course of action, just because they've already committed to it. The bias is particularly pronounced when such behaviors are exhibited publicly.

In business, this may be exemplified by the continued investment of time, effort, or money into a project that is clearly going to fail. It’s irrational behavior caused by an inability to accept or acknowledge failure.

Examples of the commitment fallacy include:

A company continues to pour money into a project that has consistently experienced delays and cost overruns, even though the chances of the project being profitable have significantly diminished. The project leader feels compelled to move forward because they have already publicly committed to it and feels a sense of loyalty or obligation to see their initial commitment through.

A contractor decides to stick with a problematic subcontractor because they've been working together for a long time, despite the subcontractor's poor performance and negative impact on the project. The contractor is influenced by the commitment fallacy, as they are reluctant to end the relationship due to the time and effort invested with the subcontractor.

To avoid the commitment fallacy:

Regularly re-evaluate your projects and decisions based on their current status and future prospects, rather than solely on the resources you've already invested. Be objective and consider the potential risks and rewards.

Be open to admitting mistakes or changing course when evidence suggests that your initial decision or investment is not yielding the desired results.

Encourage a culture of open communication and critical thinking within your team, where members feel comfortable questioning decisions and discussing potential alternatives. This can help identify potential issues early on and prevent falling prey to the commitment fallacy.

“Winners quit fast, quit often, and quit without guilt.” - Seth Godin

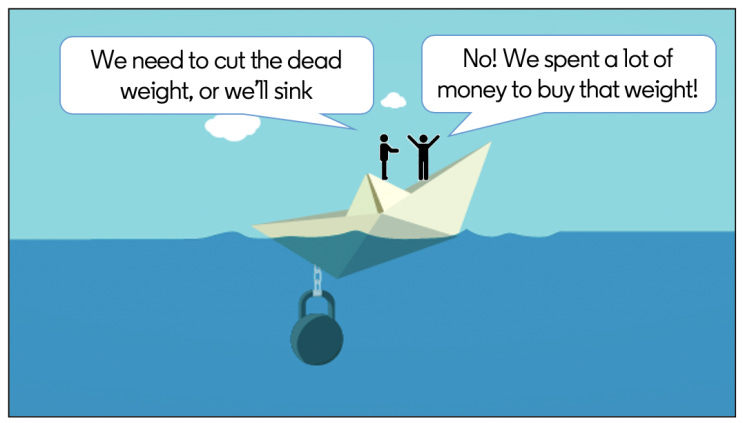

3. The Sunk Cost Fallacy

The Sunk Cost Fallacy is a cognitive bias where people continue to invest in a decision or project based on the amount of resources they have already spent, even if it is clear that the project is unlikely to succeed or that the resources are unrecoverable.

The commitment fallacy and the sunk cost fallacy are related cognitive biases, but they differ in their focus and reasoning.

The commitment fallacy is more focused on the emotional attachment to the initial decision, whereas the sunk cost fallacy revolves around the desire to justify and recover past investments.

Sunk cost fallacy causes us to ignore the promise of a better experience in the future by making an attempt to negate a loss in the past. In other words, our past investments over influence our current decisions.

This fallacy leads individuals to stick with an undesirable course of action because they don't want their prior investments to go to waste.

Examples of the sunk cost fallacy include:

A construction company has spent a significant amount of money on an innovative building material that ends up under performing. Instead of cutting their losses and switching to a better material, they continue to use the inferior product just because they've already spent money on it.

A contractor has invested substantial time and resources into a custom-designed construction solution. New information arises, revealing that a more cost-effective and efficient off-the-shelf solution is available. However, the contractor continues to use the custom solution due to the sunk costs involved in its development.

A change in direction would improve this project but I’ve already spent 40 hours doing it this way so let’s just keep it going!

To avoid the sunk cost fallacy:

Focus on the present and future value of your decisions, rather than being influenced by the resources you've already invested. Evaluate your options objectively, considering their potential risks and rewards.

Be open and willing to change course when new information arises, even if it means abandoning a previous investment. Recognize that sunk costs are irrecoverable and should not dictate future decisions.

Ask yourself these types of questions often:

Am I thinking forward or holding onto the past?

What’s the opportunity cost to continue further?

Will further investment fix the situation or cause greater loss?

“The most important thing to do if you find yourself in a hole is to stop digging.” - Warren Buffet

4. What You See Is All There Is Fallacy (“WYSIATI”)

The What You See Is All There Is (“WYSIATI”) Fallacy is a cognitive bias where people make decisions based on the information immediately available to them, without considering other possible data or perspectives. This fallacy leads individuals to jump to conclusions and make judgments based on limited or incomplete information.

Examples of the WYSIATI fallacy include:

A project manager observes a construction crew working slowly during a site visit and concludes that the crew is lazy or inefficient. They don't consider other factors, like recent changes in construction materials or methods, or the intricacies of the scope of work that may be contributing to the slower pace.

A contractor receives a low bid from a subcontractor and immediately accepts it, assuming it's the best deal available. They don't investigate the subcontractor's reputation or consider the possibility that the low bid might be an indication of low quality or cutting corners.

To avoid the WYSIATI fallacy:

Be aware of the limitations of the information you have. Recognize that your initial impressions or the data immediately available to you may not paint the whole picture. Always consider the possibility that there is more to learn or understand about a situation.

Actively seek out additional information and alternative perspectives. Consult with experts, gather data from multiple sources, and encourage open communication within your team to ensure a more comprehensive understanding of the situation.

Take the time to analyze and think critically about the information you have before making decisions. Avoid jumping to conclusions based on limited data, and instead, strive for well-informed decision-making that takes into account all relevant factors.

Thanks for reading! Want to work together?

📣 Want your product or service featured in this newsletter?

Sponsor 'The Influential Project Manager' and directly engage our dedicated community of 2,000+ construction pros. They trust our weekly insights to boost leadership and project success.

☎ 1-on-1 Coaching

Are you interested in diving deeper into a particular topic or strategy? Book time with me for a 1:1 coaching or strategy session.

🎙 Interviews

Occasionally I guest appear on podcast shows to discuss leadership, construction project management, and continuous improvement. If you have a show and interested in interviewing me, feel free to get in touch.

📧 Support this Newsletter

The Influential Project Manager articles will remain free, but if you find this work valuable, I encourage you to become a paid subscriber. As a paid subscriber, you’ll help support this work.